Since the beginning of 2022, Ukraine has seen an unprecedented escalation of cyberattacks against civil society and government sectors by Russian actors: from targeted phishing with malware to redirection of Internet traffic via Russia.

In this report, we consider the attacks that Digital Security Lab has detected or worked on.

Targeted Phishing Attacks with Malware and Attacks against Media Websites

As of July 28, a total of 230 attacks had been recorded in Ukraine since the beginning of the year.

The number of attacks increased in January, and their nature and goals also changed. Previously, civil society organizations would mostly receive phishing emails aimed at credential stuffing. Now, the more common aim is to send malware meant for information destruction or for tracking.

On January 13, Microsoft reported the spread of Whisper Gate malware, which encrypted data access on devices with Windows OS. It was discovered in systems of dozens of government and civil society organizations and private companies. However, there could be many more.

At first glance, Whisper Gate looked like typical ransomware that encrypted the Master Boot Record and demanded cryptocurrency for decryption. In fact, however, the program overwrote the MBR without a recovery mechanism. Whisper Gate was meant to disable devices and prevent access to information.

During another phishing campaign, Ukrainian organizations received phishing with malware through emails with the subject “Court request No. ####” from “Sloviansk City District Court.” The emails were allegedly sent from the domain court[.]gov[.]ua. The email requested financial information and to fill out a form via a link, which led to an archived file disguised as PDF and containing malware for Windows OS, enabling attackers to control the device remotely.

Researchers have linked some of these attacks to Russian state actors, such as Gamaredon. Microsoft wrote on their blog that since October, they had been watching Gamaredon attack Ukrainian companies and organizations, including civil society organizations. Attackers sent phishing emails with links to fake websites or malicious files, often disguised as regular documents (*.doc, *.pdf, *doc.exe). Attacks are mainly aimed at either gaining access to confidential information, tracking victims, or destroying important data.

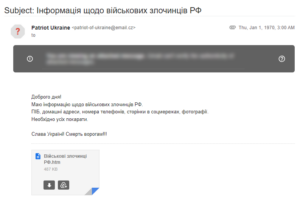

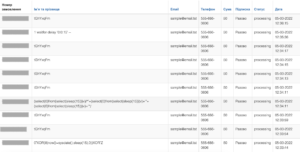

In April, the Digital Security Lab observed increased numbers of phishing emails targeting human rights groups and state structures, with the subject line “Information on Russian war criminals.”

CERT UA also worked on this incident.

“The email contains the HTML file ‘Військові злочинці РФ.htm’ (‘Russian war criminals’), which, if opened, created a RAR archive ‘Viyskovi_zlochinci_RU.rar’ on the computer. This archive contains a shortcut file ‘War criminals destroying Ukraine (home addresses, photos, telephone numbers, pages on social media).lnk,’ which leads to an HTA file containing VBScript code, which, in turns, downloads and launches the PowerShell script ‘get.php’ (GammaLoad.PS1).

The task of the latter is to determine a unique computer identifier (based on the computer name and serial number of the system disk), transfer this information for use as an XOR key to the control server using an HTTP POST request, and download, XOR-decode and launch of the payload.

This activity has been linked to the UAC-0010 (Armageddon) group,” reported CERT UA.

DDoS and other attacks on government and media websites have become another common type of cyberattack in the public space. According to the report by the Institute of Mass Information, which, among other things, documents Russian war crimes against journalists, between February 24 and July 24, Russians carried out 37 cyberattacks against media websites.

In a previous report, IMI wrote that “as a result of the attacks, media websites’ operations are suspended for a certain time completely, or they only operate partially. The attackers change the materials, upload the Russian flag, their symbols Z and V, etc.”

For instance, in March, the IMI reported daily attacks on its website since February 24.

In one case, the attackers tried to find a vulnerability by writing scripts in the form of donations. However, due to the high degree of protection of the IMI website, they failed.

Russia’s War in Ukraine as Sensitive Content for Social Media

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, blocking of Ukrainian content and accounts on social media has become much more common.

Previously, the Digital Security Lab recorded cases of content blocking mainly in the accounts of journalists and public figures with a large audience. This way, attackers tried to block information sharing and disrupt the communications of these people, since Facebook is the main social network in the civil society sector.

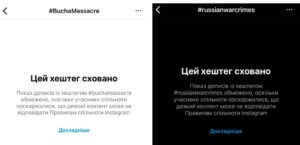

The liberation of Kyiv oblast from occupiers and discovery of atrocities committed by Russians in the occupied cities were followed by first mass blocking of publications, accounts, and even hashtags #buchamassacre, #russianwarcrimes and others. Meta reported it was a problem with the algorithm, and most accounts and posts were indeed eventually unblocked. The company also temporarily changed its hate speech policy for Ukraine.

On April 12, Ukrainian human rights organizations approached Meta with proposals on content moderation in armed conflicts. In particular:

- adopt necessary amendments to the Community Standards by introducing an exception to the rules on violence, nudity, etc.

- upscale Meta’s content moderation efforts and improve its moderation practices concerning the areas of ongoing armed conflicts.

- continue applying warning labels and blurring effects to the graphic content in question without removing it.

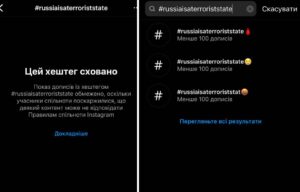

However, we continue to observe content related to Russian war crimes being blocked. For instance, after yet another shooting of civilians, the hashtag #russiaisaterroriststate gained popularity online, and it was also hidden in Instagram search.

In some cases, there are no obvious grounds why publications are blocked other than their relation to the Ukrainian context. For example, Instagram deleted the story of famous Ukrainian blogger and volunteer Serhii Sternenko with a photo of the fallen activist and soldier Roman Ratushnyi.

While Facebook and Instagram tend to block content, Twitter is more prone to blocking users — popular bloggers and volunteers. The Ukrainian Twitter community organizes campaigns asking Twitter to unblock their accounts. However, this clearly doesn’t work.

In addition, the Digital Security Lab recorded cases when social media pages of charitable organizations were cloned. Attackers falsify the pages of foundations that raise funds, putting their bank details instead.

For example, using the regular blocking of Ukrainian pages, fraudsters created fake accounts of the largest charitable foundation “Come Back Alive” on Twitter, claiming it was a “backup profile.” This stopped after the foundation’s account was verified.

The Digital Security Lab was also approached by charitable foundation Voices of Children, which has been helping war-affected children since 2015. The page of the organization was often cloned, the details were changed and, as a result, fraudsters took advantage of the organization’s credibility. The Digital Security Lab tried to help verify the foundation’s Facebook and Instagram accounts to reduce risk. But the problem could not be solved either through partners or through these organizations directly. Currently, there are no effective tools to help verify accounts, prevent such incidents, as well as effectively respond to them and quickly block fraudulent pages, so the issue persists.

Incidents in the Occupied Territories: Searches, Reception Problems, Traffic through Russia

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Russia temporarily occupied some new territories of Ukraine. People who try to get to cities controlled by Ukraine or remain in the occupied territories are regularly forced to go through searches which include inspections of phones by the occupiers, including social media, conversations, contacts etc. Any information indicating a Ukrainian identity meant a risk of confiscation or destruction of equipment or, in a worse case, beating, capture, or even death.

Such inspections of phones are most common at checkpoints and in filtration camps. People who have something connected with love to Ukraine, support of the country, interest in politics on themselves are not allowed to go through or are sent to the territory of the occupied “DPR”/”LPR.”

ZMINA human rights organization has shared the stories of people who underwent filtration and reasons for delays:

- “…I was taken to the district police office. They read all my correspondence there, the military man in the office was sitting and scrolling through my conversations for about two hours. He saw a photo of me at the elections and said, ‘How could you go there, you had Nazi authorities.’”

- “In several such locations in Donetsk oblast they held a volunteer from Dnipro, Ihor Talalai. He was detained at the checkpoint between Manhush and Mariupol, when he was evacuating people, and the reason was the Ukrainian keyboard layout on his phone.”

Some other stories of Ukrainians who have experienced filtration camps have shared by BBC:

- A 28-year-old marketer from Mariupol was brutally beaten over a video with Volodymyr Zelenskyy on his Facebook page.

- A 34-year-old history teacher was taken to the camp because he used the word “ruscist” in one of his messages.

- Russian soldiers took away the wife of a civil servant from Mariupol because she had liked the page of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

- A 60-year-old woman had a machine gun put to her face for a photo with the flag of Ukraine on Facebook and the caption “Ukraine above all.”

These stories can go on and on, but there are several specific conclusions we can draw from this:

- any information can be a trigger for the Russians;

- the Russian military does not have “guidelines” according to which they decide in which case not to let people through checkpoints, take them prisoner, etc. That is, it depends on the military servant who checks the device and on external factors.

All this considered, there is no single procedure that can guarantee passage through the filtration. Therefore, we work individually with each person who applies to the Digital Security Lab for assistance. However, the following problem arises here.

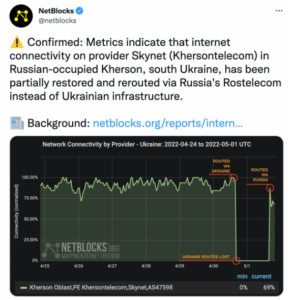

No Reception, Internet Traffic through Russia, and Potential Interception of Communications

In the occupied territories and in the areas of hostilities, there is a constant problem with damage to communications infrastructure. What is more, in May, it was reported that Russia redirects Internet traffic through the Russian communications infrastructure. The NetBlocks company, which monitors disruptions in Internet operation, reported an almost complete disconnection of the Internet in Kherson oblast on April 30. The connectivity was restored within hours, but various facts indicate that the traffic is now going through Russia.

Thus, communications in the occupied parts of Kherson oblast are probably undergoing Russian regulation, censorship and control.

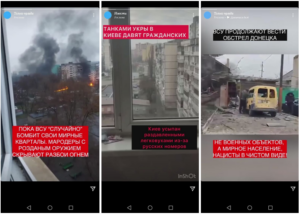

Propaganda via Social Media

In the first months of the full-scale war, the Digital Security Lab was contacted by users from the territories bordering the front line. They noticed a new type of malicious activity: empty pages without followers were created on Facebook and Instagram with characteristic names: Only Truth, News, Power in Truth, etc. After their creation, they launched paid advertising targeting the Russian-speaking population of the south and east of Ukraine, depicting alleged atrocities of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Evidently, such advertising messages were intended to incite enmity. Some of these accounts were deleted by Meta after it was approached by the Digital Security Lab. However, some of them continued to function, and it is quite difficult to prove any connection between them.

Remote Attacks on Accounts through Old Russian Emails

In the first days of the full-scale war, the Digital Security Lab was approached by journalists with requests for help in restoration of their Facebook accounts. They were mostly hacked by restoring the password through primary or backup emails on Russian domains (mail.ru, yandex.ru, etc.).

In 2017, the Ukrainian government blocked access to a number of Russian resources, including social networks VKontakte and Odnoklasniki, which enjoyed quite a big user base in Ukraine, as well as mail.ru, yandex, rambler and other mail services.

Because of this, Ukrainians mostly changed their emails. When the primary email is replaced on Facebook, the previous address becomes a backup one, which is not always obvious due to the nature of the interface. Therefore, the users usually have little idea that their old Russian (badly protected) email is still linked to their account.

We faced such incidents even before the start of the full-scale invasion, but the first month of the full-scale war was the peak.

Unfortunately, the attackers could not be tracked, because access to accounts was lost, and to restore them, we had to send requests directly to Meta.

Findings

Before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion into Ukraine, the country had quarantine restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, similarly to the rest of the world. This forced the civil society to adapt to remote work and start using new tools for communication, joint work and storage of important information. Such “training” helped many people to quickly find their bearing in the new extreme conditions and persevere in their activities.

However, overall, the war negatively affected the work of many businesses and civil society organizations, especially in the east of Ukraine, the site of active hostilities, or in the temporarily occupied territories. Some of the organizations we work with have lost equipment, funding, or cannot work because their employees were forced to evacuate to various parts of Ukraine or abroad, while some remained in the temporarily occupied territories. Some of the organizations have partially or fully redirected their work towards providing for the needs of the military or humanitarian aid to civilians.

During the full-scale invasion, digital risks of the civil society sector have significantly changed and increased, particularly in the temporarily occupied territories. Previously, there were no significant risks of physical searches in Ukraine, and their consequences were not as serious as violence, captivity, or death.

As for remote risks, we see a transformation of phishing attacks: while previously it was mostly credential stuffing, now, the attackers aim to infect devices with viruses to destroy information or spy.

Blocking of accounts on social media has become much more widespread: before the full-scale invasion, this was mostly experienced by journalists and activists due to the nature of their activity. Now, this problem can affect everyone who writes about war crimes committed by Russians, which the world should know. Unfortunately, the efforts of Ukrainian organizations and the Ukrainian government have fallen somewhat short so far, so we must significantly ramp up pressure on tech companies to change their policies and standards, which evidently are not in line with the challenges of armed conflicts. At the same time, the moderation of advertising content with blatant propaganda is at a rather low level.

The increase in the number of fake accounts posing as civil society organizations or media requires establishing stronger liaisons with tech companies concerning verification of these organizations’ original accounts, since social networks do not always verify accounts even if they comply with all the requirements.

Organizations that have left the occupied territories or areas near the front line, which have fully or partly lost equipment and other available technologies, require special support. Restoring equipment to continue activities often requires resources which the organizations do not have. The Digital Security Lab assumes that in the future, requests for basic equipment (computers, telephones, network equipment, etc.) may continue growing.

The Digital Security Lab is a Ukrainian civil society organization in the field of digital security and Internet freedom.